At 2:45 a.m. on Monday, August 6, 1945, a propeller-driven, four-engine Boeing B-29 Superfortress aircraft lifted off from the unassuming island of Tinian, its destination due North. Inside, as was customary for the B-29, was a bomb. However, unlike the bombs with which the US Air Force had scorched Japan for roughly a year, this bomb was not filled with the usual incendiaries. Rather than isobutyl methacrylate or its more famous kin, Napalm, this bomb was packed with two masses of highly enriched uranium-235. The bomb, named “Little Boy”, was anything but: snout-nosed and weighing in at 9,700 pounds, it resembled nothing more than an obese metal baseball bat. At 8:15 a.m. local time, poised above Hiroshima’s Aioi Bridge, Little Boy dropped.

44.4 seconds later it detonated. 60,000 people died instantly. 31,000 feet above, and 10 and a half miles away from them, Paul W. Tibbets, en route to Guam, felt a 2.5g shockwave driven before a kaleidoscopic pillar of smoke and debris. He felt no regrets.

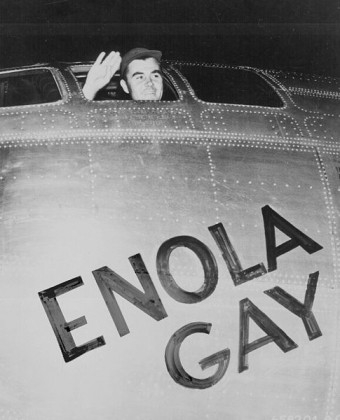

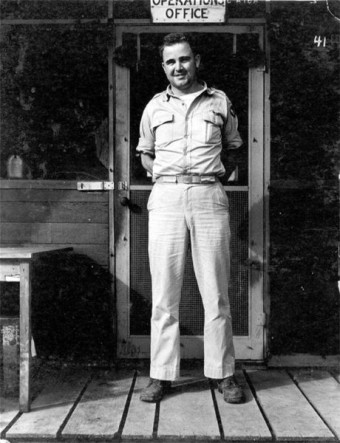

Brigadier General Paul W. Tibbets, pilot of the Enola Gay, dropper of Little Boy, recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart and four Air Medals, was born February 23, 1915. The young Tibbets performed his first flight at the age of 12, dispensing candy bars to a crowd at the Hialeah, Florida racetrack. Bitten by the flying bug, Tibbets, in February 1937 enlisted in the army. His flight instruction performance at Randolph Field, San Antonio, Texas showed him to be an above-average pilot.

Upon graduating as a second lieutenant, Tibbets first stint was as personal pilot to George S. Patton, allowing him to rack up over 15,000 hours of flight time. Tibbets ascended rapidly through the ranks, becoming a captain with his first command by 1942. In 1942, Tibbets ran the gauntlet at Lille, flying lead in a 100-plane raid with a 1/3 casualty rate. Despite the seemingly heavy losses, this was seen as a qualified success, proving that US Air forces would not break under stubborn opposition. Promoted to lieutenant colonel by November 1942, Tibbet’s cut his teeth further during the war in Northern Africa, flying Eisenhower to Gibraltar for Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North Africa.

By 1943, Tibbets had earned himself as reputation as a seasoned and senior pilot, one vouched for by Eisenhower himself. After testing the newly-minted Boeing B-29 for a year, Tibbets was recommended to Major General Uzal Ent for consideration, for a “special mission”. In September 1944, Tibbets became responsible for the organization, training and command of a secret unit, Silverplate, the Air Force wing of the Manhattan Project. Tibbets was tasked with ironing out the logistical and technical kinks: requesting modifications to bomb bay doors, in order to accommodate the bulky weapon, organizing crews with photography and scientific equipment, to record the event for posterity and finally, deciding that he himself would drop the atomic bomb.

Upon receiving orders targeting the cities of Hiroshima, Kokura and Nagasaki, as the primary, secondary and tertiary targets of the nuclear strike, Tibbets readied his crew. At 2:15 am, they were airborne. The rest is history. Tibbets, recollecting the sight of the boiling cloud in his memoirs, wrote, “If Dante had been with us in the plane he would have been terrified!”

Three days later, Major General Charles Sweeney dropped the bomb on Nagasaki. Sweeney was well prepared, flying five rehearsal test drops as well as co-piloting the support and observation aircraft for the Hiroshima bombing. Nonetheless, Sweeney’s flight performance on August 9th had none of the aplomb that Tibbets had displayed. First, the night before, Sweeney’s B-29, named Bockscar, had malfunctioned, with the reserve fuel bladder failing to pump. Running on 600 gallons less of fuel than expected, Sweeney nonetheless decided to go, intending to rendezvous with his two escort aircraft at 30,000 feet near the island of Yakushima, a fuel intensive task at that height.

Due to confusion at the rendezvous, for which Sweeney would be reprimanded later, valuable time was lost. The crew finally reached Kokura only to find it partially obscured, which was problematic given the clear directives to conduct a visual, rather than radar, bombing. After two unsuccessful flyovers, and running low on fuel, Sweeney opted for his second target: Nagasaki. Sweeney’s bad luck was Kokura’s good – indeed, so much so that the phrase “Kokura luck” has entered into the Japanese lexicon. With desperately little fuel left, and heavy cloud cover over Nagasaki, Sweeney decided drop Fat Man by radar, despite his orders to the contrary. The resulting 1.5-mile inaccuracy spared Nagasaki a great deal of damage, with the surrounding hills intercepting much of the blast. With only 60 percent of Nagasaki destroyed and two engines kaput from fuel exhaustion, Sweeney made a rough landing in Okinawa, with just seven gallons of fuel remaining. To say Tibbets was unamused by Sweeney’s near-failure, would be an understatement. However, the close-shave success was sufficient to ensure that no action would be taken against Sweeney.

Post Nagasaki, both men have been unshakeable in defending the dropping of the bombs as right and proper. Tibbets remains “convinced that we saved more lives than we took,” and concludes, “It would have been morally wrong if we’d have had that weapon and not used it and let a million more people die.” Sweeney, in his memoirs, made similar assertions, but drew fire for factual inaccuracies in his account of events. Indeed, so indignant was Tibbets at Sweeney’s account, Tibbets added a chapter to his own memoirs, in which he vented his displeasure at Sweeney’s command of the bombing.

Sweeney died at age 84 on July 16, 2004 at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Tibbets died at age 92 in 2007, in his Columbus Ohio home.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy:

Bonus Facts:

- Paul Tibbets claims in his memoirs that the code name “Fat Man” referred to Winston Churchill, but Robert Serber who worked on the design project and actually named the bombs, claims in his memoirs that it was named after Kasper Gutman, “The Fat Man”, in the film The Maltese Falcon. Although, Serber also has been recorded to have said the names simply came from the size and shapes of the bombs.

- Only one person, Lt. Jacob Beser, flew aboard the aircraft on both the Hiroshima and the Nagasaki atomic missions.

No comments:

Post a Comment